The Mt Lawley Teachers College story is essentially a story of the coming of age. For the most part, the students were post war babies. Mostly they did not come from money and often, were the first in their families to be afforded a tertiary education. Tertiary education, before Gough Whitlam, was too expensive for most. There were a lot of women in the course, partially due to the fact that there were few professions open to women at this time. Students were given a small stipend and bonded to the Education Department for three years. If you did not teach for the requisite number of years, you were expected to pay part or all of this money back. These are some of the thoughts of the students of this time.

Ruth Shean:

While we weren’t pub attendees at lunch time, we did enjoy the greater freedoms which went with post-school studies. Some lecturers regarded us as school kids — which we pretty much were — but others were very encouraging of our transition to a tertiary environment.

I have mentioned that we were generally a diligent group. When we did sewing, we were all required to prepare samples of knitting, crochet and embroidery. Most of us had done sufficient of this at school to be proficient, but set about dutifully working on our samples, often during other lessons. It is not difficult to sew, knit or crochet while listening. This became very popular, until large groups of students would happily proceed with their stitching work during all sorts of lectures. After a while, there was a polite request that we desist from such behaviour. I believe that some lecturers felt that we were not giving their topic our full attention.

There was a group of us girls who hung our together — Heidi Gfeller, Cathy Abe, Jo Nieuwkerk. I was of the view that if we worked as hard during the day as we possibly could, we would have more time to do the things that we wanted to do after hours. So we were frequently found working together, during lunch times and other breaks. We were a collaborative team who worked really well together on grouped class assignments. We would divide up the research, go off and do our own pieces of work, bring it back together and work out how best to join it up, then someone would write it up in a single hand. I don’t think that I ever had to do the handwriting, because I was as bad at writing as I was good at grammar. It was round about this time that I realised my study would be well served by my learning to type. By the time I left MLTC, I was a proficient if unorthodox typist. To this day, my typing is still unorthodox, but fast and reasonably accurate.

We all did different majors so in our third year we didn’t share all of our class time together, but still hung out with each other for the most part. Add to that, we were all away the full term of long-term prac at the start of third year [1973 for us] so all the friendship groups broke up a little. I did music and photography. I was already a pianist, but enjoyed recorder work and joined a recorder consort — for a brief period. I was not a talented recorder player because I never managed a mellow tone.

Bobbie Smith:

I met and married the father of my two daughters, before our first teaching post in Pemberton.

Neil (Robert) Kidd:

After three hectic years at MLTC we [Bobbie and I] thought a country posting would be a bit more relaxing but we were called upon to run the inaugural Karri Karnival at Pemberton in our first year out!

Ruth Collett :

We were of the opinion you didn’t question why we had to do something – we just did as we were told. We didn’t have a course or people to compare the Mt Lawley course with. In hindsight I think we had the best 3-year course ever. It covered the important theory we needed but also a practical component, which meant we were very well prepared teachers in our first year out. I’m not saying we knew everything, but we had a lot of resources to draw on. Teacher support in the early 70s was not in the schools and you were really on your own. Today’s student teachers are getting all theory and very little practical at uni – then struggle in the first few years in the classroom.

Marjorie Bly:

At the time there didn’t seem to be many career options open to women and one had to choose a career path so early. We generally had a choice of teaching, nursing, hairdressing, secretarial work or maybe becoming an air hostess. I was allocated to the “professional” stream in first year high school so I got to do French and Social Studies B instead of typing and shorthand, eliminating secretarial work as an option. In addition teaching was a fairly typical career path for members of my family back in the Netherlands so there was some expectation that I would follow suit.

During my time at Mt Lawley Teachers College, the legal drinking age dropped from 21 to 18 in 1970, so timely! There were Friday group lunches at the Knutsford Arms, with fellow students. Alcohol may have been drunk at these lunches and the following art lessons may have been enlivened by the predictable results, including fairly vague and incomprehensible answers to questions about the theory of art. Not sure if Mr McDiven ever cottoned on.

I remember the all night assignment writing sessions after an active social life and still being functional the next day at college, or at least believing I was. I couldn’t do that now.

As a mechanic’s daughter I drove an old Vauxhall Victor that was always breaking down, usually at the most inconvenient moments. There was never a lack of students to ask for a push, though.

I existed, quite well I might add, on the $16 per week education allowance. The continuous assessment was so welcome after the stress of the previous year’s angst over the Leaving and Matriculation exams. Some of the other highlights of my time at Mt Lawley included:

trying to learn the recorder with no musical talent. I usually ended up with the triangle during group music sessions. I liked the guitar playing option much better! I wasn’t any more talented but it didn’t sound as bad.

There was also a week-long geology trip in 1971, looking for and finding fossils, with Len McKenna. There was a sociology session based around ‘nature or nurture?’ and all the research up to that date couldn’t answer the question. It still resonates with me now for some reason. There was hearing about the possibility of being posted to Widgiemooltha if we didn’t study hard enough!

I remember watching drivers slipping and sliding around the oil slicks on the RAC driver training course at the rear of the college, on the other side of Central Ave. But above all, I remember doing my long prac at Como PS and discovering the teacher of my grade 5 class to be Miss Marsh – Fred and Colin’s sister. She looked very stern but was a great mentor!

Demonstrations

A radical change to the demonstration lesson organisation was introduced at the end of 1970. Instead of confining demonstration lessons to one or two schools, a pattern was adopted, based on the individual teaching strengths of the area. Ten schools participated in the scheme. Sue Haselby indicated that some of these demonstration schools were: Mirrabooka, Yokine, Coolbinia, Tuart Hill, West Morley and Sutherland Street. Sue also provided examples of some of the notes she took. You can see these by clicking on the pdf.

The demonstration schools and 60 teachers participated to provide a more flexible pattern of lessons, a greater variety of teacher behaviour, less stress for participating teachers and generally fewer disruptions to the normal activities of the schools, teachers and pupils. A single demonstration lesson was conducted at each instance, which allowed for discussion and follow up micro teaching lessons.

In addition, this was bolstered up by the development of a CCTV system. The first stage of this CCTV system was completed in May, 1971, and the first video recording was made at MLTC, in June, using students from Coolbinia Primary. Shortly afterwards, this was followed by the first “outside” recording of a demonstration lesson made at West Morley Primary.

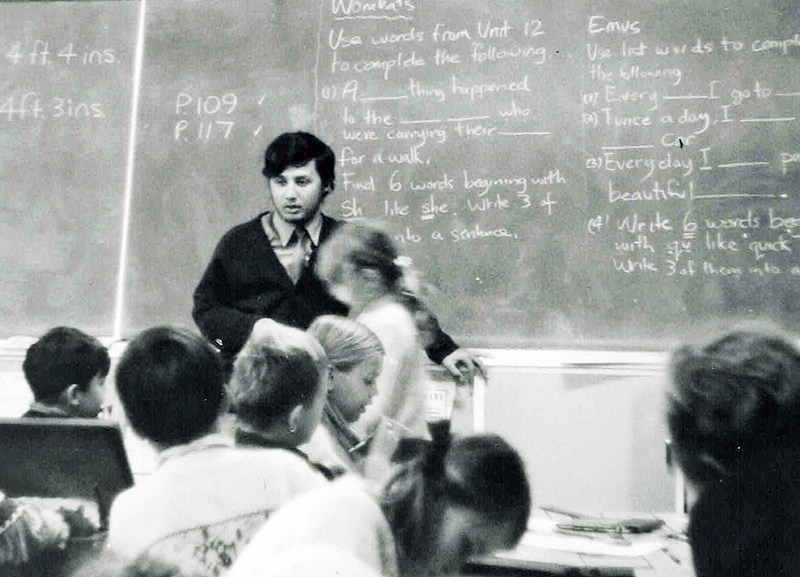

From 1971, Demonstrations were renamed “Teaching Workshops” and were conducted for everyone, one morning per week at a nearby school. These were general in nature, rather than specific. Their structure was a demonstration lesson followed by micro-teaching exercises with children at the school. On return to MLTC, there was a methods workshops and teaching peer groups with or without instant video replay.

Clive Choate:

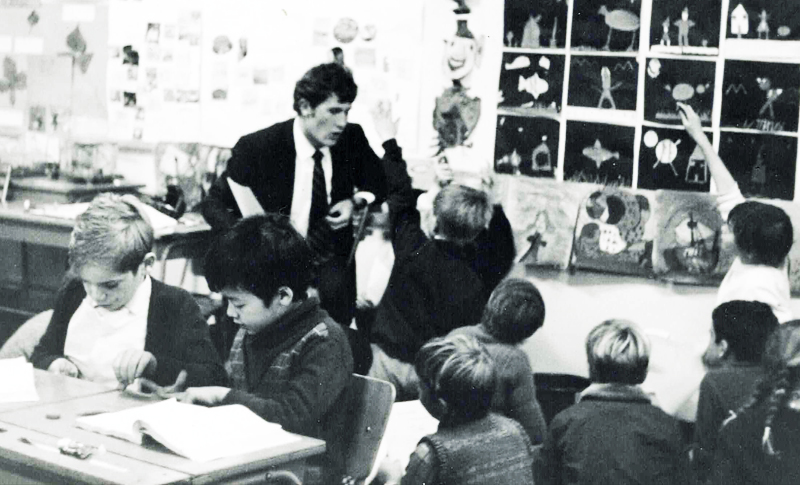

We met at many nearby schools to observe lessons after which we sat down with the teacher who talked about the presentation. To facilitate this, two trainees would supervise the teacher’s class.

We observed a variety of lessons. One that stands out was quite a failure, but a good learning experience. The teacher of the Grade 7 class was explaining Pythagoras formulae. He had prepared well with squared graph paper and obviously gone to a lot of effort. But he’d made a mistake in the size of the squares and the length of the hypothenuse! His demonstration just did not work.

Under pressure, he couldn’t work it out as he taught the class in front of a dozen trainees spread around the room. In our evaluation he was flustered and didn’t have the answers. But our College lecturer broke the ice during the debrief and reinforced that not every lesson goes well! As we found out later in life! It was a good lesson for us.

One time at a demonstration lesson day, I along with Patricia Casey of our 1K group, was left behind to supervise the Grade 1 class after observing a lesson. The children had great activities to work on while their teacher discussed the presentation with the other trainees, in the conference room.

It was a cluttered but stimulating classroom with many displays and posters, and the students were diligent and highly motivated in busy work and enthralled by our supervision. There were kids at their desks, on the mats, quite a large class too. I felt quite bad when I accidently trod on one of the tiny Grade 1s and made her cry!!

We enjoyed teaching demonstration mornings. The variety was motivating and presenting teachers were very dedicated. It was a valuable part of our training.

As we gravitated back to College in Bradford Street, we also enjoyed a further “debrief” at the Knutsford Arms which was our local watering hole for MLTC trainees!

Margaret Harris:

I have so many memories of Friday afternoon lectures with Mr Marsh in our final year. Some of our friends would go to the Knutsford for lunch and come back for the lecture. We would drive down to Dianella Plaza for our lunch. Those who had not been to the pub had the task of ensuring they kept quiet in class and were not giggling during the lecture.

I was, like most others, bonded for 3 years. This did not worry me as I had no plans to leave teaching. I actually received 2 offers of a school for my first placement. The first was at a primary school and the second was as a Physical Education teacher at Bridgetown High School. Of course I chose Bridgetown. I was so thankful that Bruce Sinclair, or someone else, had allowed me to be offered a PE teaching career.

Practicums

The Prac Department had a fluctuating staff population. This was largely due to the fact that MLTC was under the auspices of the Education Department of Western Australia, and therefore various teachers were seconded to this department for periods of 2-3 years. The constant in this arrangement, in the first four years, was Alan Jones, who was permanently assigned to MLTC. Lew Eborall was appointed in 1973 and John Love in 1974, and both of these joined Alan Jones as permanent staff until at least 1979.

The use of seconded staff supplied a variety of highly experienced teachers, who excelled in teaching and could impart their skills to the students. This also advantaged the staff involved, as it allowed them to continue employment with the Education Department and apply for promotional opportunities at the same time. Seven years after the opening of MLTC, Terry Watt and Gail Shannahan, two of the original MLTC students were employed in this role.

Before any Prac there was T.P.P.W. also known as Teaching Practice Preparation week. During this time, normal programs were suspended and assignments were arranged to allow students to concentrate on their preparation. The first day was devoted to meeting the staff and discuss the specific requirements of their teacher. Students were also able to receive their lessons a week prior, so they had a greater opportunity to prepare, with the help of MLTC staff.

By 1971, this was amended to T.P.W. or Teaching Practice Workshop. On the first day students visited their allotted school for a detailed briefing by headmasters and training teachers. The remainder of the preparation week was spent on

- Method workshops with lecturers as resource people;

- Developing detailed lesson strategies;

- Preparing teaching aids and materials; and

- Building confidence and skills.

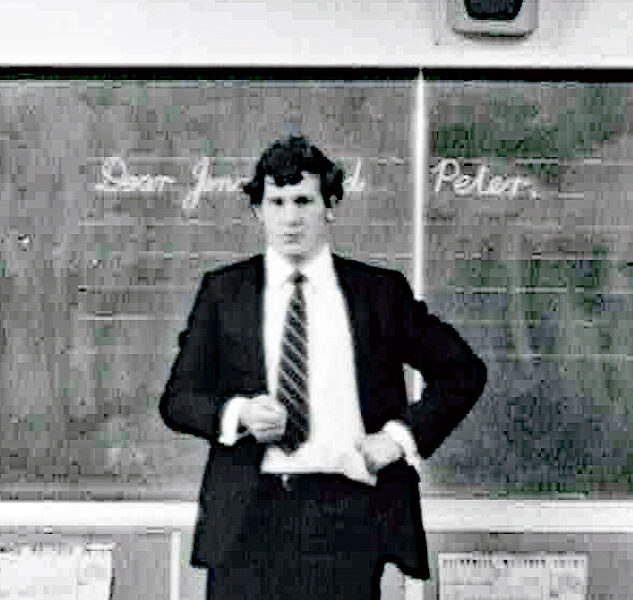

Teaching practices were important, and we looked forward to the School allocations which came from the basement at MLTC where Alistair Peacock and others presided. They were so important we traded our casual College gear for smart shirt and ties or suits, and the girls dressed up too. I achieved notoriety too on my very first teaching practice. Being keen and enthusiastic, I arrived at the school early, found a good parking place and introduced myself to the staff room where we first assembled. From there we met our supervising teacher and went to their classroom to help ready the day. “Would the owner of car XYZ please remove your vehicle from the car park immediately. You are in the principal’s car park”! I sheepishly stole past the principal’s glares as I reversed my car and let him drive in. How did I know it was his spot? It wasn’t marked, but it was a great shady bay close to the office. I still got an ‘A’ for that practice though!

I enjoyed a teaching practice at Mt Hawthorn Primary with Grade 3s. We were told the principal never visited in the first week to mark us, but as I let the children in to start the day and my first ever lesson, the serious looking principal was the last one I introduced to five rows of desks where the students stood and we exchanged pleasantries. In those days we read the word, put it into a sentence and then gave them time to spell the word in their pads.

Music was always good fun and I entertained youngsters who appreciated my piano, violin, accordion and recorder skills. One of my mates at College was not musical and told Mr True his recorder didn’t work! He agreed, especially when he discovered my mate had drilled another hole underneath it! As I did my music lessons on prac, I had quite a cacophony of music coming from the room, so much so that the principal dropped in unannounced as did a few other teachers. I gave them all percussion instruments to join in! Teaching music was fun! One practice saw my supervising teacher really struggling with a music lesson on the recorder. She was out of tune; timing wasn’t too good, she didn’t know the difference between a crotchet and a semiquaver, and it didn’t sound like the tune I could play quite well. But it was a case of saying, “no I’m not too sure about that song” for fear of showing her up! You had to be a little circumspect on teaching practice!

Formal pracs demanded lessons well written up and many nights were spent outlining goals, how we were going to motivate the cherubs, equipment/teaching aids, content, evaluation and so on. Our Lesson Notebooks were closely scrutinised by our supervising staff. I did a spelling lesson one time which I prepared meticulously with some interesting teaching aids of articles and cuttings. I highlighted in my lesson planning that they would be encouraged to have a go at difficult words, and not be embarrassed by having a go. Trouble was I spelt “embarrassed” wrong in my lesson book with one “r” and the supervising teacher delighted in crossing it with a red marker!

We enjoyed our teaching practices. Towards the end of the academic year, we did a third practice where we could request a return to our own Primary School and do a week where we taught, helped, but didn’t have to endure a formal assessment. The hosting school loved the help and I had a wonderful time at Wandarra Primary School (now called Lake Monger) where I was a pupil in the late 1950s, teaching the kids who all knew me quite well. They delighted in calling me “Mr Choate” which was different to our usual exchanges in backyard cricket in our neighbourhood!

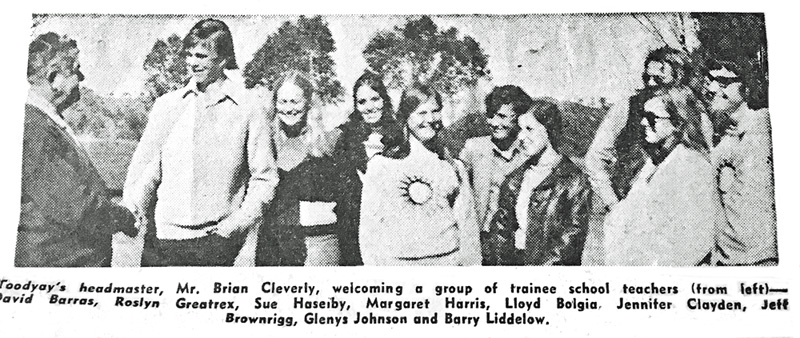

Sue Haselby: I did my country Prac at Toodyay an celebrated my 19th birthday there. I have attached a newspaper cutting of this prac (see below).

Part Time Jobs

National Service

In 1964, the National Service Act introduced a scheme of selective conscription in Australia, designed to create an army of 40,000 full-time soldiers. Many of them were sent on active service to the war in Vietnam. Despite there being a greater number of women to men in primary teaching, male students going to Mount Lawley Teachers’ College, in 1970, could be conscripted. Any of the 42 males in first intake were at risk. However, should they have been conscripted, they would have been allowed to complete their Teaching Certificate, and then sent to Officer School.